Content

- Introduction

- Architecture and Meaning in the Theory of al-Jāḥiẓ

- Architecture and poetics

- Architecture and myth.

- Al-Jāḥiẓ in the Mosque at Damascus: Social Critique

- Debate in the History of Umayyad Architecture

- Architecture and desire

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index

Preface

To understand how a specific era addressed aesthetic issues as they presented themselves to its people’s sensitivities and culture, we must examine how that era addressed these issues internally.

Instead of contributing to whatever we consider “aesthetic,” our historical investigations will be a contribution to the history of a particular civilization, viewed from the perspective of that culture’s unique sensibility and aesthetic consciousness.

To quote Umberto Eco:

When the rabbi of Rabat, Morocco, decided in the middle of the 1980s to rebuild the old synagogue of the city, he then commissioned a local architect to carry out the restoration project and asked him to give his very best proposals.

He was eager to do his best, and he made a few sketches based on his judgment of what would suit the rabbi.

The architect was a young Muslim who had little awareness of ancient Moroccan Jewish rituals. He was an architect.

When he saw the architectural drawings and their modernist approach, the rabbi could not contain his dissatisfaction.

He conveyed his dissatisfaction to the Muslim architect in the following manner:

Because we Jewish people, too, have a fondness for adornment, stucco, plaster, woodwork, and other similar elements, the community of the faithful will not be satisfied with the plain areas you are proposing, my son.

Like your people, we enjoy decorating our places of worship with lavish decorations. We prefer to have our synagogues decorated in this manner.

Unlike most Muslims, the young Muslim architect who shared this anecdote with me was surprised to discover that Moroccan Jews also shared a preference for architectural ornamentation.

However, all that is required to detect the similarities in flavor is a trip to a few classic Jewish homes in Rabat or Fes.

While the existence of this similarity may not be remarkable in and of itself, this anecdote consistently leaves my Moroccan students in awe. This is due to the strong belief that traditional ornament, with its Islamic content, must be foreign to Jewish traditions, among other styles of decoration.

In my opinion, academic scholarship plays a significant role in the widespread dissemination of this notion, manifesting in both overt and covert forms within Morocco and beyond its borders.

This is why I believe we should hold off on using the term “Islamic” to describe the architecture of the Islamic world after the rise of Islam until we have conducted more thorough research on the topic.

The preceding anecdote demonstrates that the architectural style commonly known as “Islamic architecture” bears minimal, if any, religious significance.

A complex synthesis of various legacies, as well as cultural and political statements, appears to have guided the development of the architectural styles that are currently in question.

According to Oleg Grabar, the new faith may have played a limited role in a few areas, such as the prohibition on representing living beings in religious buildings, the appearance of the prophet’s house and pulpit, and the mosque’s ritual prayer requirements.

Grabar made this observation.3) No theory of the arts can be found in the Qurʾan, which is considered the primary source of Islamic religious knowledge.

The prophetic traditions that are associated with the prohibition of images date back to the ninth century, which is a period of time that coincides with the development of the fundamental architectural typologies.

For instance, a prince dedicated the Taj Mahal, the most celebrated of these structures, as a monument to his loving wife who had passed away.

However, contrary to all assumptions, commemorative constructions do not have any religious base. According to Robert Hillenbrand, the geographic spread of the Islamic world, the mixing of different cultures, and the subsequent creation of regional styles (Ottoman, Moghul, Andalusian, Syrian, and Iranian) are all reasons why this very different style shouldn’t be defined across time periods.

A varied collection of architectural works. We should view this diversity similarly to how we regard Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque architecture, along with other European architectural legacies, as unique forms in the history of European architecture.

Additionally, it is important to keep in mind that the history of the Islamic world documents a continuous and reciprocal flow of exchanges and effects with other civilizations.

This is something that we should keep in mind. With this in mind, for example, the Umayyad architecture, despite being the product of an Islamic society, may appear to have a closer kinship to Byzantine art than to the Safavid architecture of Iran.

Similarly, the Romanesque architecture of southern France, despite its European character, may appear to be closer to Moorish art than to Rococo architecture.

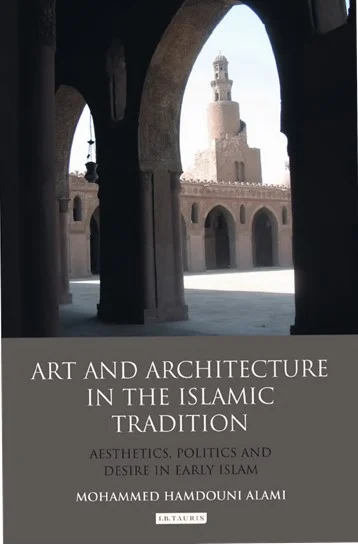

Furthermore, it is widely known that people mistake the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus for a converted Byzantine church. 5 As a matter of fact, there are still some Islamists who hold the belief that Umayyad architecture is Christian in origin. Therefore, I will restrict myself to referring to the various styles by their dynastic names.

According to K. A. C. Creswell, I would define the early Islamic period as the time when the architecture of the Islamic world was forming. This period would encompass the Umayyad and ʿAbbasid styles, specifically.

Download For Free in PDF Format